How six Bulgarians did Russia’s dirty work from the UK

BBC News Investigations

BBC News Investigations

BBC News Investigations Correspondent

BBC

BBCRoman Dobrokhotov is used to looking over his shoulder.

The Russian journalist’s investigations into Vladimir Putin’s regime – one of which unmasked the agents responsible for the 2018 Salisbury poisonings – have made him a target of the Kremlin.

But as the Insider editor waited on the tarmac to board a commercial flight from Budapest to Berlin in 2021, where he was to give evidence in a murder trial, he didn’t notice the brunette woman stood behind him.

He thought nothing of it when she took a seat close to his. Nor did he see the camera strapped to her shoulder, quietly recording.

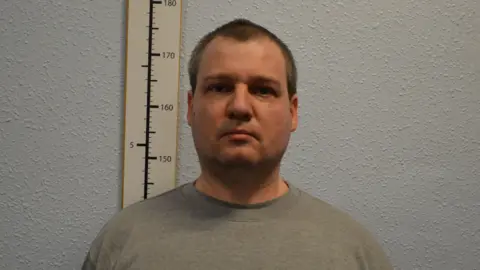

Metropolitan Police handout

Metropolitan Police handoutThat morning, the woman had flown from Luton to Budapest to locate the mark. Dobrokhotov’s flight information had been obtained in advance.

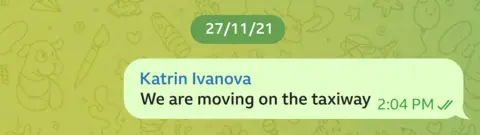

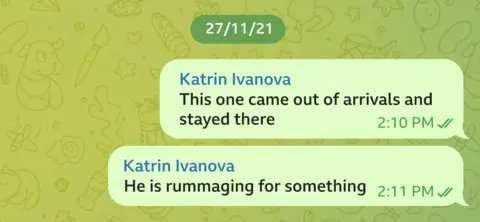

As the aircraft approached its destination, the woman, a Bulgarian – Katrin Ivanova – sent a message on Telegram.

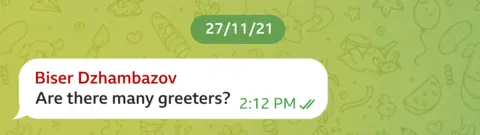

Her partner, Biser Dzhambazov, with whom she lived in Harrow, north London, was waiting for her and Dobrokhotov in Berlin.

Another woman, an airport worker identified only as Cvetka, had already flown a dummy run of the route.

Waiting in Berlin, she was another pair of eyes.

They’d lost him.

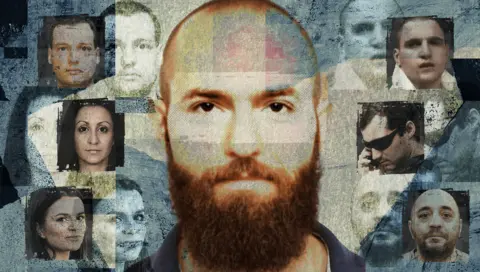

Operational for years, the cell tracked Russia’s enemies across Europe. Its leaders plotted honeytraps, kidnap and murder in service of the Kremlin. Following a trial, three members were convicted on 7 March at the Old Bailey in London for their part in the conspiracy. Three more had already pleaded guilty.

“We’re in a situation where only some of us will survive,” Dobrokhotov would later tell the BBC.

“It will be either Russian journalists and human rights watchers, or Vladimir Putin and his killers.”

Watching events in Berlin unfold from the UK was the final member of the Telegram group, another Bulgarian, Orlin Roussev, 47.

Metropolitan Police handout

Metropolitan Police handoutAn associate recalls Orlin Roussev as a man fascinated by espionage. An email address associated with him includes the 007 sobriquet of the world’s most famous secret agent.

He moved to Britain in 2009, before he set up a company involved in signals intelligence – the interception of communications or electronic signals.

When police officers searched the faded 33-room Great Yarmouth former guest house in which he lived with his wife and stepson, they discovered, in the assessment of one expert, “a vast amount of technical surveillance equipment which could be used to enable intrusive surveillance”.

They might have been less dry. It was an Aladdin’s cave disguised as a cluttered seaside relic; sophisticated communications interception devices worth £175,000; radio frequency jammers; covert cameras hidden in smoke detectors, a pen, sunglasses, even men’s ties; a horde of fake identity documents and equipment to make more. An encrypted hard drive was left open. Telegram conversations were visible on Roussev’s laptop.

Among the masses of equipment, police discovered the business card of a one-time finance executive, Jan Marsalek.

Metropolitan Police handout

Metropolitan Police handoutRoussev first met Jan Marsalek in 2015, introduced, he recalled, by a mutual acquaintance he had met at the offices of a British investor and wealth adviser. In emails from that time seen by the BBC, Marsalek enlists Roussev’s help in acquiring a secure mobile phone from a Chinese company.

PP Muenchen

PP MuenchenThen, Jan Marsalek was the respected chief operating officer of German payments processing company Wirecard. While reports criticising Wirecard’s business practices had started to appear in the Financial Times, the company’s reputation as a star performer in the European fintech sector, valued in excess of £20 billion at its peak, was intact.

Now, he was directing operations as Roussev’s controller on the run from fraud charges – the subject of an Interpol red notice – following the company’s 2020 collapse.

Together, the pair conceived operations targeting journalists, dissidents, politicians, even Ukrainian soldiers thought to be training at a US military installation in Stuttgart. They discussed selling US drones captured from Ukrainian battlefields to China. And they did it for Russia.

Linked to the state’s intelligence services, Marsalek is believed to be hiding in Moscow. He faces no charges in the UK.

The group Roussev employed, all Bulgarians, were not the spies of popular imagination.

Alongside Dzhambazov, a medical courier, and Ivanova, a laboratory assistant, he employed a beautician with a salon in Acton, Vanya Gaberova; a painter and decorator, Tihomir Ivanchev; plus an MMA fighter nicknamed “The Destroyer” who wore his fights on his face, Ivan Stoyanov.

Metropolitan Police handout and social media

Metropolitan Police handout and social mediaA neighbour who knew two of the accused was sceptical they could be guilty. They were too stupid and didn’t know anything, the neighbour asserted, though they admired the fighter’s “enormous calves”.

But they were not ineffective – Roman Dobrokhotov recognised none of the group’s faces when pictures were shown to him by police.

The group operated a clear hierarchy. Roussev reported to Marsalek, who reported to his “friends in Russia”. Roussev managed the rest of the Bulgarians, who he referred to as his “minions”, Dzhambazov chief among them.

“There are no bosses here,” Dzambhazov wrote, as he issued instructions to Ivanchev.

Nonetheless, “minion” was attached to the decorator’s number in Dzhambazov’s phone.

Metropolitan Police handout

Metropolitan Police handoutThe group dynamics were complicated. Dzhambazov and Ivanova were in a long term relationship and lived together. Gaberova and Ivanchev were in a relationship until 2022.

But it was Dzhambazov and Gaberova police found in bed together when they burst into the beautician’s northwest London flat in February 2023.

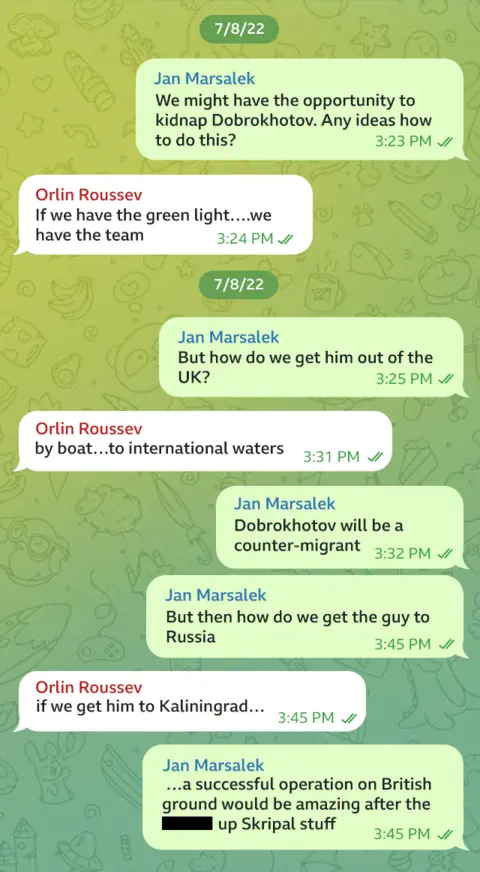

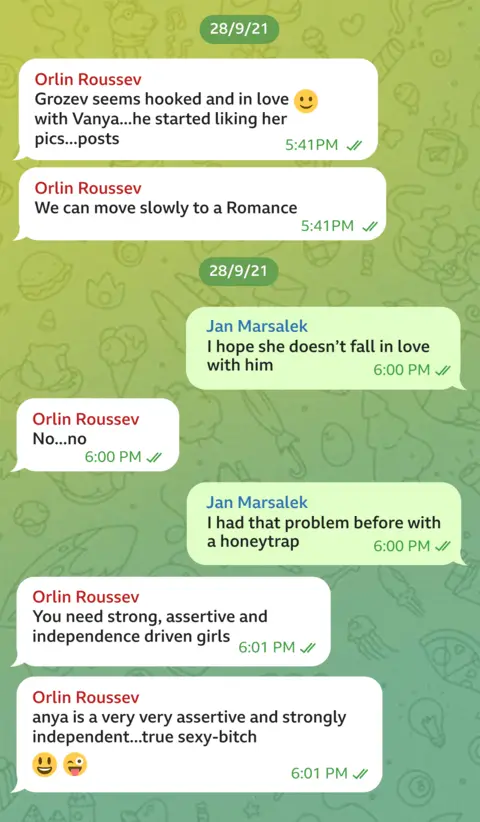

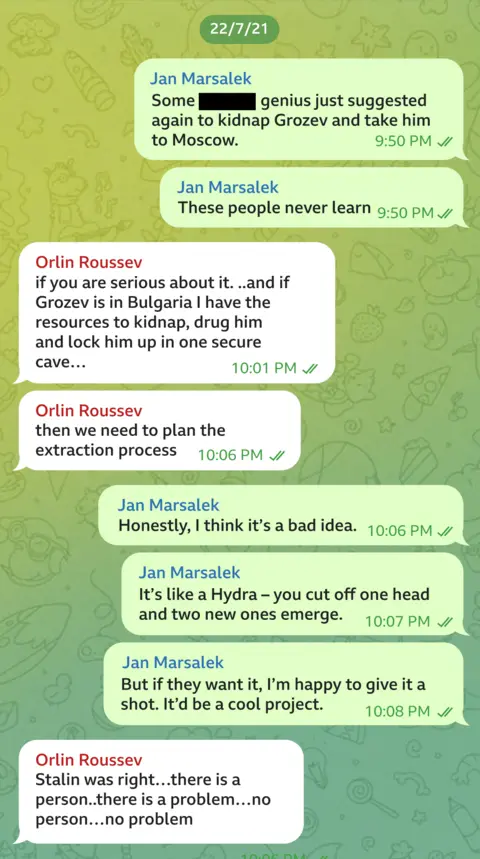

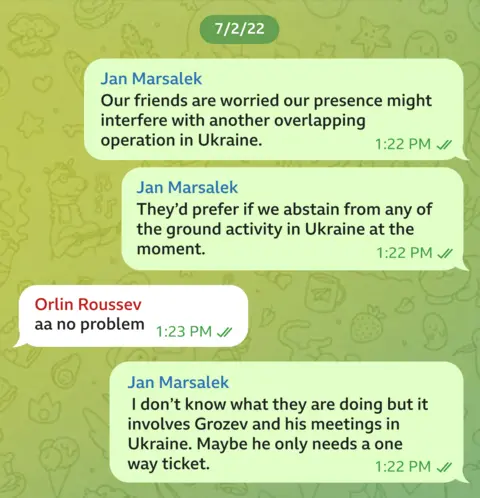

Between August 2020 and February 2023, Marsalek and Roussev exchanged 78,747 messages on the Telegram messaging app.

They reveal at least six operations the spy cell was tasked with over a period of years – four of which targeted individuals who were enemies of Putin’s regime.

As well as Dobrokhotov, the Bulgarian investigative journalist Christo Grozev was watched at home in Vienna. Cameras in the window of a rented apartment nearby were trained on his front door.

Metropolitan Police handout

Metropolitan Police handoutHe was tailed on flights and photographed in a Valencia hotel eating breakfast with co-founder of the Bellingcat investigative collective Elliott Higgins.

A thorn in the side of Russian intelligence services, he was observed in Bulgaria meeting with an arms trader who had been the victim of an assassination attempt Grozev linked to the Russian state.

Gaberova was instructed to befriend him.

In Montenegro, the cell searched for Kirill Kachur, who had worked for the Investigative Committee of Russia until he fell foul of the Kremlin. They were anxious to impress. A second Russian intelligence team circled, including a chain-smoking blonde woman referred to only as “Red Sparrow”.

Kirill Kachur/YouTube

Kirill Kachur/YouTubeMarsalek and Roussev discussed the kidnap and murder of both Grozev and Kachur. It wasn’t an empty threat – a colleague of Kachur’s had separately been taken to Moscow.

A former Kazakh politician living with refugee status in London, Bergey Ryskaliyev, was targeted at a luxury apartment in Hyde Park. Further reconnaissance took place at his home.

Bergey Ryskaliyev/Facebook

Bergey Ryskaliyev/FacebookIvan Stoyanov, who acknowledged his part in the conspiracy, was spotted parked in a Toyota Prius outside his address. Suspicious, an assistant of Mr Ryskaliyev noted the licence plate.

When confronted, the MMA fighter claimed he was working for a Kensington hospital, delivering tests. The next day, an NHS logo had been placed in the windscreen.

Prosecutors said providing information on a political dissident like Ryskaliyev “is predicated on Russian attempts to control diplomatic relations”.

Indeed, Marsalek would further task Roussev with another project: a hare-brained scheme to initiate a staged protest at the Kazakh Embassy featuring blood dropped from drones, an astroturf human rights campaign involving Just Stop Oil, a letter addressed to the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen, advertising on London buses and unrealised deepfake pornographic video of the Kazakh president’s son. Russia would then help nervous Kazakh security services “uncover” the “activists” responsible.

In February 2022, Telegram exchanges between Marsalek and Roussev reveal a preoccupation with following Christo Grozev to Kyiv, where he was believed to have travelled.

Their offers to help were rebuffed.

Fewer than three weeks later, Russian tanks surged across Ukraine’s eastern, southern and northern borders.

Later that year, Marsalek asked Roussev if one of the cell’s three IMSI grabbers – sophisticated communications interception equipment – could be deployed to spy on Ukrainian soldiers in Germany. Roussev promised to retrieve it from his “Indiana Jones garage”, where it was “gathering dust”.

Metropolitan Police handout

Metropolitan Police handoutMarsalek returned to the idea repeatedly.

By February 2023, Roussev and Marsalek were plotting to send Dzhambazov and “one more person” to Stuttgart, where they believed Ukrainian soldiers to be training on Patriot missile systems.

![Telegram message exchange between Jan Marsalek and Orlin Roussev dated 1 and 2 February 2023. JM writes: "Apparently 70 Ukrainians arrived in Germany to train how to use the Patriot air defence system... another set of candidates for your IMSI project". OR responds that he will "send Max and 1 more person on Wednesday 8 February to Germany for the 2 IMSI-ies. We aim at been operating [sic] Wed-Thu next week".](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/480/cpsprodpb/f204/live/81fb5dc0-eafb-11ef-bd1b-d536627785f2.png.webp)

Had they successfully deployed and captured Ukrainian troops’ mobile phone data as planned, they might have used it to pinpoint those same troops on the battlefield – leading Russian forces to Western-supplied Ukrainian air defences.

“This was espionage activity of the highest level of seriousness,” prosecutor Alison Morgan KC told the jury at the Old Bailey.

Before their plans could be put into action, they were arrested – Dzhambazov, Ivanova, Gaberova and Stoyanov in London, Roussev in his guest house.

Though Ivanchev identified himself to police outside Gaberova’s flat, he would not be arrested for another year.

In his first police interview, he told officers he had spoken to MI5 in the interim. The interview was paused.

None of the six denied their actions.

Roussev, Dzhambazov and Stoyanov pleaded guilty before trial. Ivanova, Gaberova and Ivanchev denied knowing they were working for Russia.

The jury disagreed.

Ivanova, Gaberova and Ivanchev were found guilty after the jury deliberated for over 32 hours. Ivanova was also found guilty of possessing multiple false identity documents.

They could face up to 14 years in prison. They will be sentenced in May.

But it is not the end.

“If there is no regime change, there will be new and new teams of people who come to kill or kidnap you,” Roman Dobrokhotov told the BBC.

“This is this actually something that motivates us to work.

“From the very beginning, I was sure it was something directly controlled by Vladimir Putin.

“In his dictatorship you would never take responsibility on your own to do such political stuff.

“You’d always have a direct order from the president.

“Putin is a psychopath who has no borders,” he said.

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/8ccc/live/85e1e1b0-e232-11ef-a319-fb4e7360c4ec.png

2025-03-07 15:36:27